If you manage projects using a simple list of tasks, you’ve probably experienced the “phantom bottleneck.”

It looks like this:

Lists are great for telling you what to do. They are terrible at telling you when it fits.

A Gantt chart is how you stop guessing and start scheduling. It takes a static list of “to-dos” and spreads them out across a timeline so you can spot reality before the deadline hits.

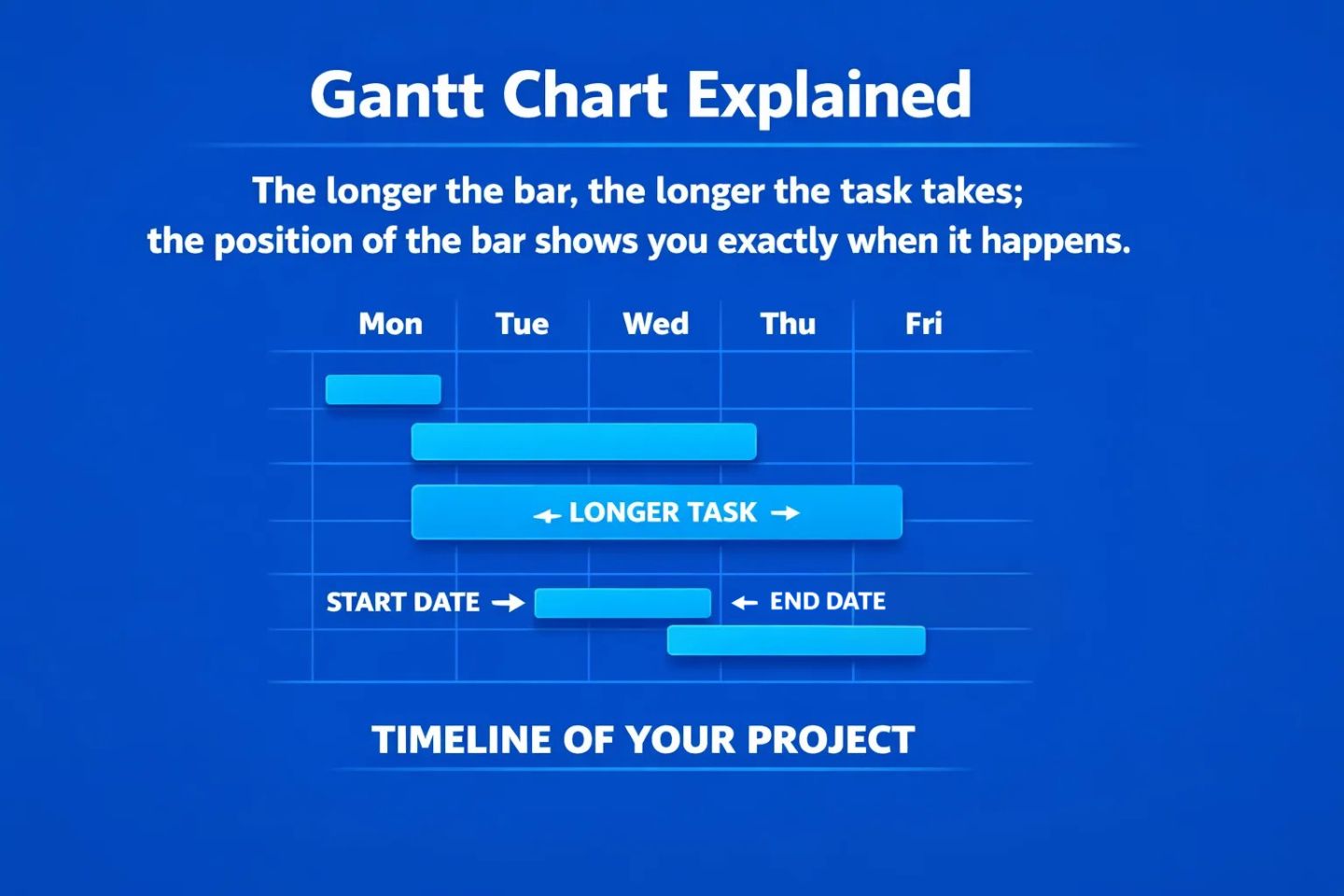

A Gantt chart visualises your project schedule by turning tasks into horizontal bars:

“The longer the bar, the longer the task takes; the position of the bar shows you exactly when it happens.”

Think of it like a calendar, but instead of just showing meetings, it shows the lifespan of every piece of work on your plate.

Most project data starts in a table:

| Task | Start Date | End Date | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Write Code | 01/02/26 | 05/02/26 | Sam |

| Test Code | 04/02/26 | 06/02/26 | Sam |

If you look closely at that table, you might spot a problem. Sam is supposed to start testing the code before he finishes writing it.

In a list, that conflict is just two dates hiding in a grid of numbers. You have to do mental maths to find it.

In a Gantt View, that conflict screams at you. You would instantly see two bars overlapping for Sam, showing a physical impossibility.

Lists hide time. Gantt charts reveal it.

While they can look complex, every Gantt chart is built from the same four simple ingredients:

Across the top runs your time. This could be days, weeks, months, or quarters. This is your “playing field.”

Every task is a horizontal bar.

These are the arrows connecting the bars. They tell the story of the workflow. An arrow pointing from Task A to Task B says: “You cannot start B until A is finished.”

These are zero-day events. They aren’t work; they are finish lines. Examples include “Project Sign-off” or “Beta Launch.”

It’s named after Henry Gantt, an engineer who popularised this way of visualising work in the 1910s (originally for factories and infrastructure).

While technology has changed—we aren’t drawing these on paper anymore—the core principle remains: visualising time is the only way to manage it.

Here is why project managers eventually graduate from spreadsheets to Gantt views:

“We said this project would take 2 weeks, but when we drag the bars out, it physically takes 4 weeks.”

“Why is Sarah assigned to 5 active bars in the same week? We need to move these.”

“We can’t paint the walls until the plaster is dry.” If the plastering takes 2 extra days, a Gantt chart with dependencies will automatically push the painting task back 2 days. (We’ll cover how Gridfox handles these “Strict” vs “Flexible” moves in a later post).

Sending a client a list of dates is confusing. Showing them a picture of the timeline makes them understand why the launch date is set for March.

Gantt charts are powerful, but they aren’t for everything.

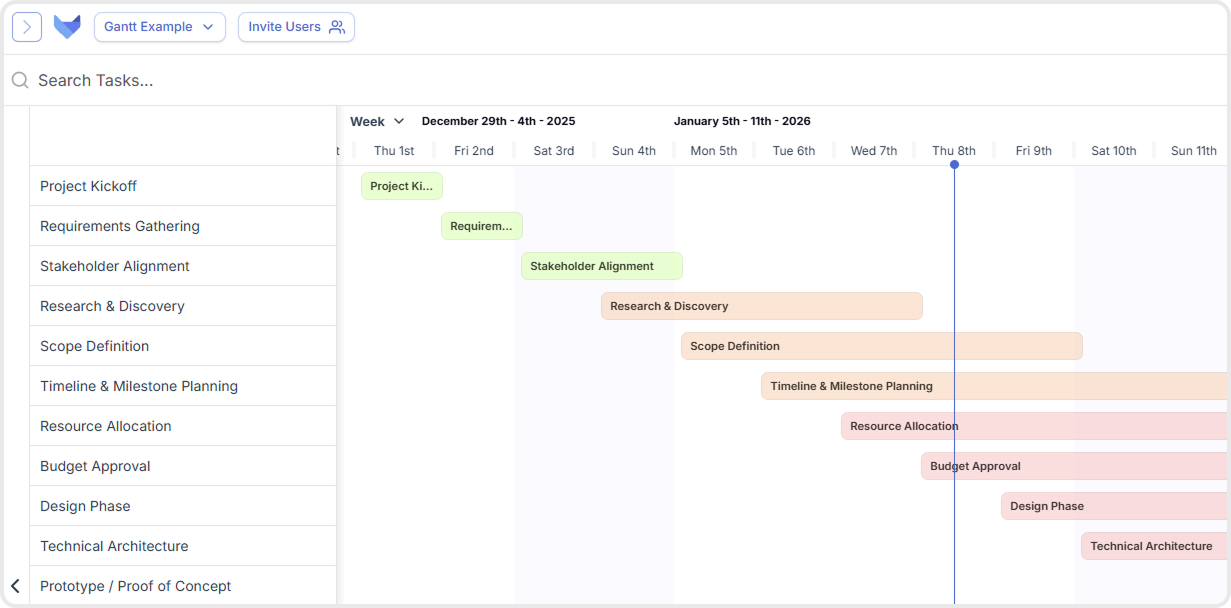

In Gridfox, a Gantt View isn’t a separate island, it’s just another way to look at your existing data.

If you have a Table of tasks with a Start Date and an End Date, you are one click away from a Gantt chart.

(We’ll walk through the exact setup steps in the next post.)

Look at your current project list. Pick three tasks that are related.

Ask yourself:

If you can’t answer that instantly, you need a Gantt view.

Next up: We’ll show you how to build your first Gantt View in Gridfox in under 2 minutes—including how to add those handy status colours and assignees.